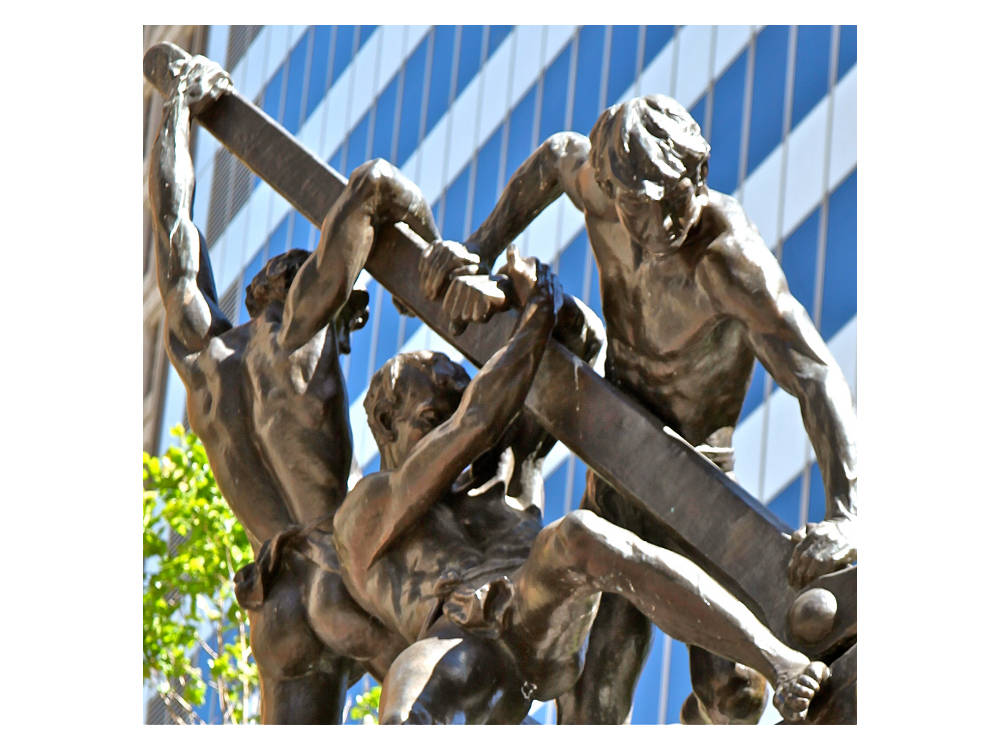

[Bending the moral compass : statue, Lower Market Street, downtown San Francisco (2013). Photo by torbakhopper, under Creative Commons]

A senior professional in London who was exploring a career transition to management consulting says he has changed his mind after reading a story in The New York Times. Studying for an executive MBA, he was set to join one. The story, As McKinsey Sells Advice, Its Hedge Fund May Have a Stake in the Outcome, was published on February 19, 2019. It is a troubling account of the conflicts of interest of well-paid consultants who advise firms on their business strategies while, at the same time, making investments in various forms of financial enterprises to multiply their own wealth. Though the story is about the iconic McKinsey & Co, founded in 1939, it is also a comment on the management consulting industry. It raises deep questions about the ethics of business enterprises.

The foundations of the management consulting business were laid by venerable men, including Marvin Bower of McKinsey and Bruce Henderson of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG). They enjoined consulting companies’ partners to be trusted advisors of chief executives, and to give objective advice to improve the performance of their businesses. Before them was Dr. Arthur Dehon Little of MIT, who created a consulting company in 1886, Arthur D. Little Inc (ADL), to assist businessmen to turn scientific ideas into commercial products to serve society’s needs and make business profits. Other consulting firms emerged from ADL, such as the very successful BCG (1963) and Bain & Co (1973), and also grew. Management consulting became a very respected profession. Business school graduates, selected by the leading strategy firms, got the highest salaries—and those by McKinsey the most of all.

I worked with ADL in the USA from 1989 to 1999. Those were heady days for capitalist enterprises. Socialism, or at least communism, was supposedly dead with the fall of the Soviet Union. Stock markets rose. New computation technologies powered the dotcom boom. Young people were becoming millionaires overnight without spending years slogging as consultants.

An existential challenge

For some of the ‘best of the best’—management consultants with McKinsey, Bain and other firms—this was an existential challenge. If they were so smart, why were they not earning as much? Some left to start their own ventures and made it good. Since smart people are the only resources of any management consulting company, the firms had to come up with ways to retain them. A transformation of consulting companies began, from being trusted advisors of their clients, into creative enterprises that would enable their partners to partake in the gravy of the capitalist boom.

The heady changes in the consulting industry also affected ADL in its quiet campus in Acorn Park, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where its consultants were exploring new technologies and management solutions for their clients. ADL could not offer graduates the same financial rewards that the others were. It had a different business model. Whereas the others sought to make their clients dependent on them, building long relationships from which they could draw large streams of fees, the ADL philosophy was to do the job and leave until invited to return—no hanging around. It wasn’t a financially lucrative strategy for the consulting firm. So, ADL began to rethink its consulting strategy to emulate the extended engagement model of the others, at which McKinsey was the best.

But even this model was not sufficient to produce the new wealth McKinsey’s partners wanted to earn to keep up. So, as the NYT reports, they began to explore other avenues which, as road leads on to road, seem to have brought them twenty years later to Guernsey Island and other tax havens and into law courts to defend their integrity (read about NYT’s coverage here). New investment vehicles were created for the partners to invest in business ventures. New entities were also formed in which consultants could invest their sweat equity along with their money. Thus, webs of ventures grew within which the financial interests of consultants became tangled with their professional ethics. McKinsey has not been able to convince the courts that the Chinese walls between these ventures were strong enough to keep the consultants focused solely on their roles as trusted advisors of their clients, the purpose for which their eminent founder had created the firm. (McKinsey maintains that there was no wrongdoing.)

The partners of management consulting companies were confronted with ethical dilemmas while adapting to the paradigm that the ‘purpose of a business is to increase shareholder value’, and with it, the culture of ‘more wealth is better’ (and even ‘greed is good’) that began to spread across the capitalist world in the 1990s. When the partners of BCG met to approve a proposition to create a vehicle for partners to invest in technology startups, a young partner stood up. He said he wanted to ask all partners to consider why they had joined the firm. For himself, he said that he had been inspired by the call to be a ‘trusted advisor’ who would help business leaders to do good things and do them well. The way to make money he said was that clients must value our advice and pay for it. We must not get diverted from the mission to pursue more wealth for ourselves, he urged.

The debate within ADL was more divisive. The firm had many wise old-timers who had spent their lives relishing the intellectual challenges their clients gave them. Their satisfaction was in finding innovative technical and managerial solutions, and in helping their clients to produce value with those solutions. NASA was among ADL’s largest clients. ADL’s environmental practice was one of its most successful—in the 1990s, long before the threat of climate change compelled businesses to pay more attention to their impact on the environment. The new partners, many of them ‘laterals’ from other consulting companies, were impatient. They wanted to earn more money. ADL had troves of intellectual property. They wanted to monetise it and produce more wealth for the partners. They made innovative new deals with investors to carve out the monetary value. The conflict between the heightened pursuit of money with the ethical values of many consultants caused a one-hundred-year-old firm to implode.

“You have to decide, am I a consulting firm or an investment firm?” the February 19 NYT article quoted Charles Elson, a finance professor at the University of Delaware who focuses on corporate governance. “They’re two different things.”

Faulty measures of success

A medical doctor is expected to be a trusted advisor with only the patient’s interest in mind. A doctor who encourages the patient to use more investigative and therapeutic services, thereby increasing the revenue stream from the client, is not working in the client’s best interests even if the services provide some marginal value to the client. If the doctor has a financial stake in the provision of these services, one would even consider this unethical practice.

Whenever doctors and hospitals become ‘businesses’ such ethical issues will arise. They arise for the media too, which is expected to work in the public interest, when media becomes a business. The ethical question for all professionals—doctors, journalists, and management consultants—is, what is the purpose of the service they provide to their clients and to society? Is it to produce more returns for themselves, or to increase their clients’ and the public’s well-being? The simple answer is—both.

But life is never so simple. When the pursuit of more wealth takes over, the original purpose of the enterprise becomes compromised. When the principal measures of the success of an enterprise become how large its revenues are, and how much wealth is made by its investors (or, in the case of a consulting business, its partners), society loses something. It loses enterprises and professionals with integrity that can be trusted to maximise their clients’ gains. The timber of institutions that society used to look up to cracks.

The technology industry is going through a big existential crisis for this reason. It was much admired for the exciting new innovations it created. Social media that enabled people to reach out. Search engines that enabled people to find any information they wanted. Apps to get instant gratification. Their owners have become among the richest persons in the world. Within a few years of these enterprises being seen, naively, as God’s gifts to mankind, their dark sides have become exposed. The purpose of these enterprises was never to provide a public service. It was to create more wealth for their owners.

Management schools teach people how to get things done efficiently. There is very little introspection in schools about the social purposes for which the skills learned should be used. In fact, what business schools have been teaching is that the principal measures of success of a business are how much value it can create for its shareholders by efficiently extracting value from the environmental and societal resources it uses. Businesses are ranked by their shareholders’ wealth and by their revenues. These are self-referential, even selfish, measures of success. The success of the business is not gauged by the positive impact it has on the lives of people and on the environment.

Even large, not-for-profit organisations in the social sector use such self-referential measures to determine how effective they are. Their boards examine how much the budgets of their organisations are growing. They set goals to double and triple their own sizes, presuming that if they become larger the world will benefit. Much less time is spent by their boards to reflect on the value their organisations actually provide to society, and to find ways to increase their beneficial impact while remaining small. Catalysts of improvement in the world around them—social sector organisations and trusted advisors—do not have to be large themselves. They must learn to induce improvement in the world with minimal increase in their own size.

When the budgets of organisations become large, it is only a small step to justify larger salaries for their managers. CEO salaries are often a small percentage of the budget. So, as the budget grows, it becomes easy to justify higher salaries and lose sight of the purpose of the enterprise. Recently, one of India’s largest and most admired trusts lost its tax exemption because its CEO was earning about $300,000 per annum. The charity commissioners felt such a high salary, which a large, profitable business could have justified, was not in line with the charitable purpose of the organisation.

There is nothing evil about wanting to be wealthy. The question is, how wealthy does one need to be? If the answer is, to be as wealthy as others, which is what seems to be driving the behaviours of many professionals, doctors and consultants, the race is on, in an upward spiral, in which the wealthy look for ways to become even wealthier. Somewhere in the spin along, they lose sight of the original purpose of the enterprise and also lose their ethical moorings.

Business schools are rated by the salaries their graduates are offered by employers. Employers compete with each other to hire from the best rated schools. The best schools attract the best students. Thus, in a reinforcing cycle, money becomes the measure of success for students. The ‘best of the best’ are tempted to join professional firms driven by the same measures of success. In such cultures, principles of service, societal trust, and ethics become hard to learn and hard to teach.

I find many young people wanting to opt out of this culture, like the senior professional in London who has changed his mind about joining a consulting firm. Many business schools are searching for ways for their students to acquire an ethical orientation. And some consulting companies are trying to return to their ethical moorings. The social and business culture of greed for more wealth, in which they are all locked, will not be easy to change. But it must be changed to make the world better for everyone.

The established order will resist changes leaders want to bring about. Thomas Kuhn’s classic, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, explained why those who are aligned with the prevalent paradigm of ideas, and are powerful in institutions founded on those ideas, will feel threatened by any powerful new idea. They will fight back.

The powerful global Empire of financial investors and shareholders will strike back at uppity business leaders who break out of the paradigm. Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever for ten years—St. Paul as he was called, reverentially by some, and sarcastically by others—was brought down by a backlash from shareholders. They felt that he was going too far in meeting the needs of other stakeholders.

Consultants advocating for more ‘corporate social responsibility’ are expected to establish the ‘business case’ for it. They must prove to business leaders that CSR will produce more returns for shareholders in the long run. Otherwise, it seems not worth it. This is the selfish, self-referential paradigm of business responsibility that must be changed. It is a struggle between the Empire and the People and the Earth. Now the Earth and the People are rumbling, contesting the power of the global financial Empire.

Leaders of change will be those who will take the first steps towards shaping a better world for everyone, regardless of whether others are following them or not. They will look inwards to rediscover the purpose of their existence. And to reset their own measures of success. They will not be waiting for others to change first, for then they will not be leaders.