[Mundra Port in Gujarat—now a critical node in India’s global supply chains. Photo: Felix Dance / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA)]

For years, Indian boardrooms operated on the comforting assumption that technology was a neutral enabler and global markets were stable, predictable, and largely insulated from geopolitics. That world has quietly vanished. As digital systems now shape everything from finance and logistics to payments, energy, and information flows, the line separating corporate risk from national security has blurred beyond recognition. The platforms that help companies scale are the same platforms foreign adversaries can exploit. The data that fuels decision-making is also a strategic asset that can shift geopolitical leverage. The infrastructure that keeps businesses running—cloud servers, payment rails, digital supply chains—has become a domain of strategic vulnerability. This is the new reality: national security is no longer only the state’s problem. It has become a core concern for corporate leadership and governance.

When Compliance Becomes Geopolitics

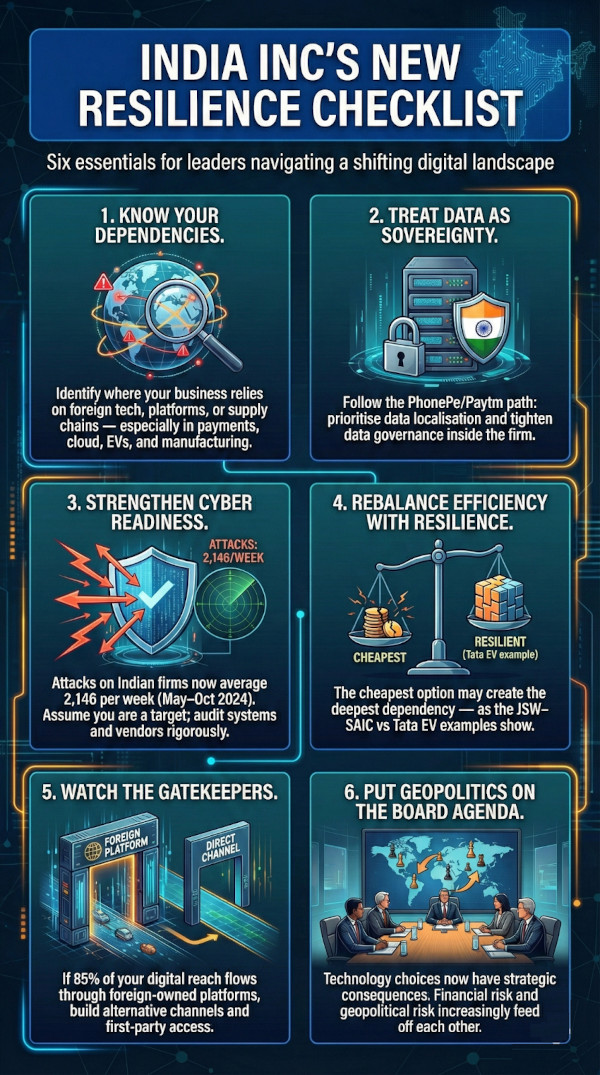

A striking example lies in the evolution of India’s fintech ecosystem. When Razorpay came under scrutiny in 2022-23 over transactions linked to foreign digital lending apps, the issue was not merely compliance. It exposed how Indian payment gateways had unintentionally become part of a transnational digital environment that regulators increasingly view through the lens of financial sovereignty. Even after the courts dismissed the charges, the larger message remained: digital platforms are not just pipes. They are strategic infrastructure with national implications. This is why firms like PhonePe and Paytm have embraced data localisation and framed it as an essential element of India’s digital sovereignty. Only a few years ago, data localisation was criticised—especially by several foreign firms—as inefficient or protectionist, and was resisted on grounds of added friction and cost. Indian fintech players, meanwhile, pushed back and argued for the strategic value of keeping sensitive data within the country. Today, the conversation has shifted. Efficiency is no longer the sole metric. Resilience—and the sovereignty that underpins it—has become central to long-term competitiveness.

The End of the Borderless Corporation

Technology was once hailed as the great integrator, the force that would flatten borders and unify markets. Instead, it has become the engine of economic nationalism. The interdependence that powered globalisation is now being weaponised. The shift is visible even in the United States, long the bastion of free markets. It is now the American state that influences Apple’s supply-chain decisions, scrutinises the ownership of TikTok, and determines what kinds of chips NVIDIA can export to China. The message for India Inc is clear: if the world’s largest corporations cannot insulate themselves from geopolitical forces, Indian companies cannot assume immunity either. Boardrooms must expand their sense of responsibility. Market share, growth, and competitive strategy still matter, but they now coexist with questions of jurisdiction, sovereignty, and strategic exposure.

Redrawing the Perimeter of National Security

The concept of national security itself has migrated. It no longer resides solely in barracks or command centres. Much of what keeps a country functioning—its logistics networks, energy grids, data centres, payment infrastructure, and digital supply chains—is built and operated by the private sector. A cyberattack on a port terminal or logistics hub is no longer just an operational inconvenience; it is an event with economic and strategic consequences. A Tata Communications report found that between May and October 2024, the average Indian organisation faced 2,146 cyberattacks per week, compared with 1,239 globally. Many of these are not random intrusions but part of a broader contest in which digital vulnerabilities are deliberately probed and exploited. Corporate security and national security have become intertwined. The resilience of a company’s systems is now part of a country’s broader strategic resilience.

Understanding the China Question

No discussion of this new landscape is complete without understanding China’s approach. Under its doctrine of civil-military fusion, the boundary between commercial innovation and state strategy has blurred. Chinese companies operate in an ecosystem where scale, speed, and state backing converge to serve national objectives. For Indian firms, this creates a structural asymmetry they can no longer ignore. Partnerships with Chinese manufacturers or digital service providers offer speed and cost advantages, but they also create long-term dependencies shaped by the strategic priorities of another state.

The electric vehicle sector shows how this tension plays out. JSW Group’s collaboration with SAIC (MG Motor) gives immediate technological benefits, but anchors its supply chain to a geopolitical rival. Tata Motors, in contrast, has chosen slower but more resilient localisation of its EV battery capabilities. The question is no longer only about growth. It is whether today’s choices create dependencies that constrain tomorrow’s autonomy.

The New Landscape of Influence and Vulnerability

This expanding risk landscape extends beyond infrastructure into the realm of information itself. With more than 85% of India’s digital advertising routed through foreign-owned platforms, the last mile of consumer access lies outside India’s jurisdiction. This introduces a gatekeeper risk that almost never figured in corporate strategy discussions. Meanwhile, persuasive technologies—powered by AI, deepfakes, behavioural profiling, and hyper-targeted nudging—can now shape public sentiment at scale. These tools pose new challenges for brand reputation, customer trust, and corporate credibility. Managing narratives is no longer merely a marketing function; it has become a strategic vulnerability.

As global digital ecosystems fracture into jurisdictional blocs, businesses must navigate diverging regulatory regimes, data flows, and compliance expectations. Data governance is no longer the domain of compliance teams; it has become a fundamental question of corporate architecture and long-term strategy.

A New Leadership Mandate

All of this points to a profound shift in corporate responsibility. Indian CEOs and boards must recognise that technology choices carry strategic weight. The cheapest option may embed the deepest dependency. First-party data, algorithmic transparency, diversified supply chains, and domestic capability-building are no longer optional. Policymaking too is undergoing a shift. The state can legislate for security, but it cannot build it alone. The private sector is now an essential collaborator in safeguarding the digital and economic systems on which the country depends.

The real challenge is one of mindset. Corporate leaders must move beyond viewing national security as an externality or a regulatory concern. It is now woven into the fabric of competition itself. Technology is the new theatre of strategic contest, and Indian firms are participants, whether they choose to be or not. The task ahead is not to militarise business thinking but to deepen strategic awareness; not to disengage from global markets but to engage with them with greater foresight; not to retreat into protectionism but to build autonomy through intelligent choices.

If the last decade was about digital transformation, the next decade will be about strategic digital independence. The companies that recognise this early—and adapt their governance, partnerships, and architectures accordingly—will not only secure their own futures but also help shape India’s. In a world where digital and geopolitical landscapes are shifting rapidly, the ultimate competitive advantage may no longer be speed or scale alone, but sovereignty grounded in resilience.