[Photo by Jens Johnsson on Unsplash]

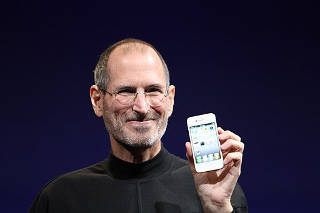

In his introduction to the brilliant biography of Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson shares something that Jobs told him. “I always thought of myself as a humanities person as a kid, but I liked electronics. Then I read something that one of my heroes, Edwin Land of Polaroid, said about the importance of people who could stand at the intersection of humanities and sciences, and I decided that’s what I wanted to do.”

Talking about his legacy, Jobs later says, “Edwin Land of Polaroid talked about the intersection of the humanities and science. I like that intersection. There’s something magical about that place.”

Watching some of the early interviews and speeches of Jobs—and these videos keep showing up on social media as a relief from the broader gloominess of our times—it’s clear how often he took ideas from that magical place.

In one video, for example, he says: “What we’re about isn’t making boxes for people to get their jobs done, although we do that well. We do that better than almost anybody in some cases. But Apple is about something more than that. Apple at the core, its core value is that we believe that people with passion can change the world for the better.”

It’s not just Apple that gets its ideas from that magical place. Many approaches that businesses and social enterprises swear by these days—Design Thinking, for example—are based on this intersection.

What next? Where do we go from here? Some of the biggest debates across the world suggest that it is the intersection of technology and society. These platforms have achieved huge scale, and have multiple consequences, good and bad, intended and unintended.

This space is magical too, in part because there are more questions than answers here. Much of the optimism about technology has settled down to a kind of cautious optimism. There is a growing realisation that we need both techies and fuzzies. There is a renewed appreciation for systems thinking.

In that context check out ‘Lessons from India’s tortuous path to make tech work for the people’, which also digs into some of the research my colleague Charles Assisi and I did on Aadhaar for our book.

Have a great week!

NS Ramnath

Featured Stories

Lessons from India’s tortuous path to make tech work for the people

[Photo from UIDAI]

India’s experience with providing a digital identity to a billion-plus people through Aadhaar and with financial inclusion shows why it’s important to take the state, society and markets along. And how it’s tough to anticipate the unintended consequences. (By NS Ramnath. Read Time: 18 mins)

The ambitious and their enemies

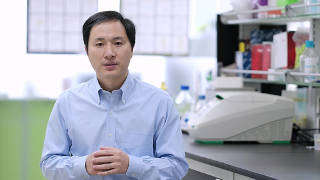

[He Jiankui. Photo by The He Lab (CC BY)]

This Week in Disruptive Tech looks at Oyo’s pitfalls on the fast track, He Jiankui and gene editing, Facebook’s efforts to build an operating system, micro-mobility, and Digital India's tech gaps. (By NS Ramnath. Read Time: 3 mins)

What We Are Reading

The changing face of economics

Economists necessarily lack evidence about alternative institutional arrangements that are distant from our current reality. The challenge is to remain true to empiricism without crowding out the imagination needed to envisage the inclusive and freedom-enhancing institutions of the future. (By Dani Rodrik)

The next big thing in transportation? The ‘un-car’

The automobile industry will look a lot like the airline industry if manufacturers don’t rethink their offerings. Enter the un-car. (By Devin Liddell)

A resolution for the new decade

Democracy is not merely a right, but it is also a responsibility—a burden to be the keepers of our Republic, not merely on election day but on every day. (By Raghuram Rajan)

From Our Archives

The technology of democracy

[Photograph from photodivision.gov.in]

Democracy is in peril with innovations in technology running too far ahead of innovations in democracy’s processes. (By Arun Maira)

Are you too old to be an entrepreneur?

[Photograph by Matthew Yohe under Creative Commons]

Some of the most admired entrepreneurs started late in life. Dr G. Venkataswamy started Aravind Eye Hospitals after he retired; Steve Jobs was 52 when the iPhone was launched. (By Rishikesha T Krishnan)