[Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

Last October, when the Chinese government descended with its full might on Jack Ma, the country's most famous businessman, and scuttled Ant’s $34 billion IPO, many believed Ma was being punished for criticising the state. Just a few days earlier, he had told a gathering that the Chinese regulations were outdated and stifled innovation. However, the more perceptive China watchers knew that it was not the first time Ma had criticised the government, and that something more serious was brewing. China was tightening the screws on Big Tech.

In the weeks and months that followed, China rolled out a series of regulations, including most recently, against edtech and online gaming. Earlier in August, new rules banned for-profit online tutoring, inflicting a decisive blow to the industry. Later in the month, regulators limited the time minors (under 18) could spend on online games to merely three hours a week. Again, while some tried to portray it as regulations on children, industry veterans deciphered the significance of the message. It was intended for Big Tech players such as Net Ease and Tencent.

Clearly, the State versus Big Tech slugfest is not playing out only in China. It is the most compelling global narrative of our times. In Europe, the stringent General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018 regulating the big players of the tech industry was a watershed moment in state regulation of technology. In the US now, the Biden administration is witnessing bipartisan support to regulate Big Tech.

It’s a global game, but it is playing out differently in different geographies. The histories and motivations are different, and the lessons are different too.

In this four-part essay, we will explore the State Vs Big Tech conflict in China, the US, and the EU, and draw lessons from there.

In India too, there are big changes underway. However, to fully understand what's happening here and the potential paths forward, it's important to understand what's happening in the rest of the world. Let’s start with China.

Tech Regulation in China

Of all the regulatory regimes, the Chinese state has been most successful in reining Big Tech. As their market capitalisation (m-cap) shrinks, Chinese tech is looking to expand to geographies with less stringent regulations. In the ten months from October 2020, the Chinese tech industry lost $1 trillion, which amounts to 10% of the Chinese stocks’ m-cap, The Wall Street Journal estimates. China's tech giant Tencent has lost $411 billion in market value since January 2021 due to the onslaught of the regulatory authorities. The new regulations have forced the management to look abroad for greener pastures by expanding its portfolio in gaming, which constitutes 7% of its total sales. Given that the gaming industry has not come under the regulators' radar in foreign markets, Tencent plans to capitalize on its strengths in this domain. The decision of the Chinese authorities on August 30 to restrict access to video games by the country's young people will further push Tencent's plans to expand its gaming business in foreign markets. This was not how it used to be even five years ago.

From Calls of ‘Mass Innovation and Mass Entrepreneurship’ to Tech Regulation

The Chinese state a few years back urged the country's youth with slogans encouraging mass innovation and mass entrepreneurship. Taking a cue from the central leadership, local officials sprung to action building innovation zones, and incubators by promoting academia-private industry partnerships. The government also backed ‘guiding funds’ to attract and encourage venture capitalists to invest in new technology startups. The government projected the major tech players like Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent (collectively referred to as BAT) as ‘national champions’. The Chinese authorities subsidized tech entrepreneurs with calls from the State Council to create thousands of tech incubators. In a short period, China built a conducive ecosystem for startups with 89 unicorns valued at $350 billion. It had 609 billionaires against 552 in the US. In the wake of the tech war with the US, the Chinese government went all out to support its tech players by giving them preferential treatment in the made in China 2025 plan.

The tide has turned from active encouragement to stifling regulatory scrutiny recently. Besides Alibaba and Tencent, Meituan (food delivery), Pinduoduo (ecommerce), Didi Chuxing (ride-hailing), Full Truck Alliance (freight logistics), Kanzhun (recruitment), and New Oriental Education (online tuition) have faced the heat from Chinese authorities.

Why did the state take this U-turn? To make sense of this, we have to first understand the rationale behind the Chinese state's attempts to control the tech sector.

According to a document jointly released in August 2021 by the Chinese Communist Party's Central Committee and the State Council titled ‘2021-25: Implementation Outline for Building Law Based Government,’ Beijing is to roll out stringent regulatory measures for a wide range of sectors. The latest document, among other things, states authorities would actively work on new legislation in areas like ‘national security, technology, and monopolies’. The regulatory authorities have been forthright in stating that the new regulations will target antitrust behaviour from Big Tech, data security overhaul, and check on ‘capitalist excesses’. The motivations can be placed into three buckets: political, economic, and social.

Political Motivations

One of the abiding features of the Chinese political tradition has been the cycle of centralization, decentralization, and recentralization. Although centralization has come too quickly in tech regulation, it has been building up over years—nationally and internationally.

“Manufacturing drove China’s economic modernization for over two decades. The leadership then decided to engineer further advancement by making China a tech-driven economy. Once the state built a critical mass, the leadership decided to take a U-turn”

Ever since Xi Jinping’s elevation as the President of the country and the General Secretary of the Party, China has seen a renewed emphasis on the 'Party First' approach. Given that the secondary sector (manufacturing) mainly drove the country’s economy in more than the first two decades of ‘economic modernization’, China’s leadership decided to engineer further advancement of its economy by making China a tech-driven economy. The state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have limited expertise, and therefore state authorities encouraged domestic tech players and promoted them as national champions in the tech domain.

The state was more than ‘a willing partner’ to the tech startups and negotiated the limits of state-society boundaries, which are otherwise very clear in the non-economic domains. It was also comfortable partnering with the private players to implement domestic and foreign policies. As a result, mobile payment apps like Ali Pay (of Alibaba) and WeChat (of Tencent) became important partners in the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) markets.

Once the state built a critical mass, the country’s leadership decided to take a U-turn and timed its swoop on Big Tech to perfection, hurting them when it mattered the most. In this regard, the state’s targeting of Jack Ma’s empire couldn’t have been timed better. The political signaling was loud and clear. Given the focus of the current leadership to ‘bring the Party back in’, it was critical to unequivocally state that no one is bigger than the party in today’s China.

“In an authoritarian state, it is unimaginable that any non-state actor has more access to information about its society in the form of data”

In recent times, the Chinese leadership realized that the wings of the technology industry players must be clipped in the nascent stage itself in the IoT world. In an authoritarian state, it is unimaginable to entertain the idea that any non-state actor has more access to information about its society in the form of data.

Signaling from the political leadership prompted the regulatory authorities to flex their muscle. Regulatory agencies like the State Administration Market Regulation (SAMR), China State Regulatory Commission (CSRC), Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), dormant till now, have jumped into action. The CSRC has developed new rules to ban Chinese companies with large amounts of sensitive data from going public in the US stock exchanges. The new rules restrict the country’s tech firms from launching their IPOs in foreign stock exchanges. Measures like this will help Beijing exert control over the complex corporate structures that were being resorted to for side-stepping restrictions on investment. The new measures necessitate approval from a cross-ministry committee to be set up primarily to investigate applications by Chinese companies for overseas IPOs.

Besides CSRC regulations, the CAC has become very active too. Founded in 2014, it was mainly mandated to censor the country’s internet behind the Great Firewall and rarely involved with domestic companies’ plans to go public. Of late, it has come up with new restrictions on overseas IPOs by Chinese startups.

China’s ministries too have become proactive in regulating the tech industry depending on the issue. For instance, the industry ministry has mandated that the apps created by the tech industry follow and maintain specific standards. And the education ministry has been very keen on introducing regulatory measures for online tutoring services. The labour industry has called upon the internet platforms to give dignified treatment to gig workers. The SAMR, established in 2018, has become proactive in penalizing those violating antitrust regulations (Alibaba was fined $2.8 billion). Some of the other tech players have been fined for failure to disclose mergers and for signing exclusive contracts. It is worth noting that the antitrust law in China has been in existence since 2008. Still, strict compliance has only started since the SAMR introduced new regulatory measures to rein internet platforms.

In short, the Chinese state gave a long rope to tech companies, and let them venture far and wide as long as they served the party’s political needs. But the other end of the rope was firmly in the state’s hands.

Economic Motivations of Tech Regulation

The China-US tech war has prompted the Chinese state to put national security interests above anything else. Investment in its technological infrastructure and reducing dependence on foreign players has seamlessly integrated with China’s counter-cyclical spending following the Covid-19 outbreak. According to Bloomberg, China has allocated $1.4 trillion to be spent over the next six years. Many of these funds will support technological conglomerates like Huawei to lay the fifth-generation wireless networks, install cameras and sensors, and develop AI software. The long-term strategic goal is to help domestic firms Huawei, Digital China, Tencent, Alibaba, and Sense Time Group outcompete US companies in the tech sector. A few years back, as part of the country’s ‘mixed ownership’ reforms, the Party leadership was keen to infuse private players to rejuvenate the state-owned enterprises. Of late, mixed ownership is being given a new meaning where the state itself is keen to acquire some of the start-ups in the tech domain and ally with them to achieve national security objectives. This policy is in sync with China’s goals to become self-reliant in science and technology as per the 2035 plan.

“China is keen to build advanced technological abilities to become a tech superpower. To promote R&D in core technology areas, the state is rolling back tax benefits enjoyed by the Alibabas and Tencents”

China is keen to build advanced technological abilities to become a tech superpower. Policymakers realize that building a ‘hard tech’ necessitates building technical infrastructure, which will boost its self-reliance. This policy translates to self-reliance in manufacturing semiconductors, ‘industrial internet’ and not consumer internet. To promote R&D in core technology areas, the state is rolling back tax benefits enjoyed by the Alibabas and Tencents of China. The policymakers are now keen to encourage investments in semiconductors, ‘core critical technologies’ and promote domestic companies’ patents and IPRs. In this regard, new stipulations are being laid out to employ qualified people. For instance, the tech companies are being asked to have at least 40% of their workforce comprising an undergraduate degree.

“Such measures might be bitter medicine for the domestic tech companies, but in the long run, it will stand them in good stead and make them future-ready to face competition from their Western counterparts”

Further, such organizations are being encouraged to employ 25% of their total workforce as R&D professionals. The tech companies have been mandated to have 7% or more of their total revenues for their R&D expenses. Such companies are being lured with tax incentives, whereas the same is bound to dent the earnings of ecommerce giant Alibaba and internet giant Tencent. Experts contend that such measures might be bitter medicine for the domestic tech companies, but in the long run, it will stand them in good stead and make them future-ready to face competition from their Western counterparts.

In addition, some policymakers argue that monopolistic positions enjoyed by the domestic tech companies since 2015 have dented their ability to come up with innovative products and have hurt their prospects to compete at a global level. Further, policymakers in China believe that the big-ticket IPOs might lead to bubbles and the locking up of people’s hard-earned savings to be squandered once the bubble bursts. Beijing is also keen to discourage the lure of superstar entrepreneurs who generate unrealistic investor expectations to generate stock market bubbles.

Social Motivations of Tech Regulation

The economic modernization project in China since 1978 has seen millions of people pulled out of poverty. However, Chinese society has also witnessed the problem of regional and inter-personal income inequalities. These inequalities led to a shift in focus from economic governance to social governance since the 21st century. Under the previous President Hu Jintao construction of a ‘harmonious society’ was accorded priority. During the leadership of Xi Jinping, the ‘China Dream’ project, anti-corruption measures have been launched as part of the leadership giving importance to the supremacy of the Party. Under Xi’s leadership, the party has redoubled its efforts to identify itself with the common person’s aspirations to boost its political credibility. The current techlash in China is inspired by these objectives as well. Authoritarian accountability has necessitated the state to respond to broader public disenchantment and discontent.

“Under Xi’s leadership, the party has redoubled its efforts to identify itself with the common person’s aspirations to boost its political credibility. The current techlash in China is inspired by these objectives as well”

For instance, the tech domain’s exploitation of gig workers like food delivery workers, the 996 (working from 9 AM to 9 PM, six days a week) in the tech domain has threatened China’s social fabric. This exploitation has forced the government to come hard against what is being called ‘disorderly capital expansion’ (wu xu kuo zhang). The unbearable stress has given rise to disenchanted youth who have started opting out of the rat race and lie flat (tang ping). A growing clamour of Chinese youth to opt for inner reflection (nei juan) and take it easy has led the government to encourage the youth to work hard. Sensing that it is not enough, the state is determined to empower workers and the disadvantaged. ‘Common prosperity’ is being given a prominent place in the political discourse and is being highlighted as an ‘essential requirement of socialism’. The state is coming down hard on tech players who have been exploiting gig workers. For instance, the party-state has taken recourse to criticizing Big Tech players with what is being called ‘reputation sanctions.’ Such a ploy will dent their brand image by leveraging state media and impacting their stock price.

Moreover, it has prompted the Big Tech players to join hands with the government to eradicate poverty and boost legitimacy. The State - Big Tech alliance will help gain the government some legitimacy and is bound to improve the brand image of Big Tech players. Perhaps the state is conscious that a technologically powerful China is not possible without the private players.

The recent crackdown of the Chinese state against Big Tech in China has raised some concerns. To what extent will it stifle the innovative abilities of domestic tech players? Given the tech prowess that the domestic companies are capable of, is the Chinese state hurting its prospect of becoming a tech superpower by zealous regulations and in the process alienating its tech industry players? How does the West look at the various facets of Big Tech regulation? Are the concerns of the EU regulators different from that of their American counterparts? What are the motivations of the EU in regulating the Big Tech companies from the US? What are the various challenges in implementing tech regulation in the Western markets? Does tech regulation in the West have geopolitical implications in the US-led West’s tech war with China? I will try to examine some of these issues in the following parts of this four-part essay.

Read parts 2-4 of this series on State Vs Big Tech:

- Part 2 on the drivers for regulation in the EU

- Part 3 on taming the American giants

- Part 4 on splinternet and the geopolitics of tech regulation

Editor’s Note

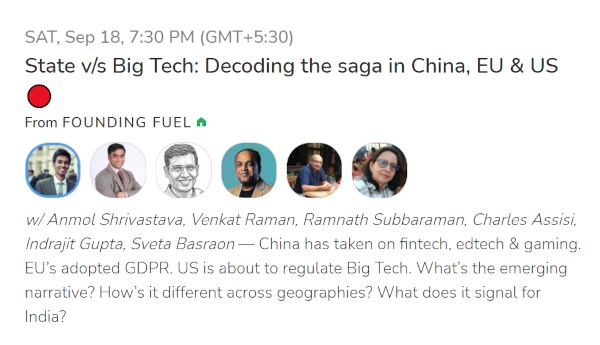

Join G Venkat Raman on Clubhouse for a chat on State Vs Big Tech: Decoding the saga in China, EU & US. Time: Saturday, September 18, 7.30 PM (IST)