[Photo by Edward Howell on Unsplash]

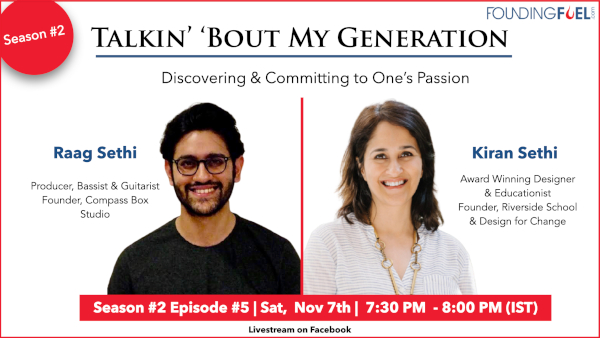

By Raag Sethi and Kiran Bir Sethi

Everyone has role models. It could be a scientist, an educator, artist, musician, sportsperson, leader, actor, author, the occasional politician—the list is long. Their passion seems to be a common trait that qualifies them as our idols. Now, I’m sure there’s plenty more responsible for their achievements and contributions to society than the gross simplification of passion, but if you run through your personal list of mentors and role models, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone with passion omitted.

Typically, the only way to follow someone you look up to is the internet—and it’s possible you will never meet your idol. I have been very fortunate to have two from my list with me my entire life. My father, 10-time world Billiard Champion Geet Sethi and my maverick educator mother Kiran Bir Sethi.

It’s hard to quantify, with any reasonable metric, what it means to be passionate about something, and harder still to replicate it. The conditions and circumstances that permit the growth of passion is elusive and nonconforming. Is it obsession? A larger sense of purpose? Is it perhaps desperation? No one really knows and the research is inconclusive, so I can only speak from my experience what has allowed me to find mine, and how to continually combat environmental conditions like this pandemic, and commit to a passion.

You’d think that in a household like ours, passion would come easy, or better yet, be handed down as if it were hereditary.

My father was my first peek into excellence, which is strange considering I didn't even understand the fuss around his success. Cue sports was an obscure activity and didn't have the pizazz of tennis or cricket. There were relatively few Indians playing it and fewer still that had the resolve to call it a sport and not just a hobby. He broke ground and records by devoting himself to the green baize. And at the same age that I was figuring out what to major in college, he had won his first world title. It's still ridiculous to think someone can be the ‘world’s best’ in something in their early 20s.

This not only gave me my first definition of passion, but also a benchmark and timeline for success.

My mother, on the other hand, has gone through two very different professions—as an interiors designer and as an educator. But I would argue, the passion has remained unchanged—it’s just that the conduit changed from spaces and aesthetics to children and impact. Her design phase lasted from her early 20s to her mid-30s. She then made a drastic shift from having a design studio to constructing a school. Without a background in education or cognitive theory, she decided the next best thing after a design studio was a school.

Through them, I was witness to two versions of passion. One that is steadfast and all-consuming like my father’s, and one that is more malleable and adaptable like my mother’s.

Growing up I remember not being pressured or coerced to follow my father’s cue or continue on as a designer like my mother—unlike my friends who came from more traditional families where the expectation was that they will continue in the family business.

This meant my early childhood was spent mainly trying out everything without mastering anything, which was markedly different from my parents. I was interested in physics and astronomy, theatre and music, English and history. Even when applying for college, I went in undecided; I hoped the four years of my undergrad would give me some direction on what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

My mother supported this. She knew that I needed time to figure out the things that make me happy. Which brings us to a popular fallacy: what you decide now is permanent and irrevocable.

I graduated with a major in Integrated Educational Studies and minored in classical guitar. The idea was to come back home after my graduation and work at my mother’s school since I enjoyed teaching. Music was a hobby and more importantly, too risky to commit to. I didn’t know anyone professionally in the music industry, nor did I have a background in music production or audio engineering. I felt it was unrealistic both as a vocation and as a passion. While I did play the guitar, the idea that I could make music for a living was never a conversation anyone had with me.

This harkens back to my memories of what my father also went through when deciding to pursue Billiards. He was in a similar position where there wasn’t really any scope or hype around professional Billiards. Most people probably saw it as a hobby. Despite that he committed to it without worrying about feasibility or the future.

I worked at the school for years, and thoroughly enjoyed every bit of it. It gave me the space and time to work with people (an important skill for anyone) and allowed me to go deeper into the disciplines I loved to learn—history, music, English, math and physics. I became more empathetic and felt an obligation to be in the service of others. The pretence that music was something important in my life slowly diminished as I grew more into the role of a teacher.

It was only about four years ago that I started realizing the merits of playing music.

I had just formed a band, and got the basic equipment required to start recording music. This was more of a “hey, let’s see what’s possible” approach than a conscious decision to become a musician. I think the moment was when I was playing and making original music with my band and we found ourselves performing at the mecca of live music in India, the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai.

This transition phase from teaching to music was anxiety-inducing. I was aware that I was starting really late in music. And the fact that I had something good going at the school was constantly weighing on my mind. I was caught in the pros and cons. I soon discovered that pros and cons are rarely part of the discourse if what you are doing is making you happy. And music made me happy. I distinctly remember my mother telling me how I seemed to find music more enjoyable than school work as I “never had to be reminded for music”, alluding to the fact that I constantly needed reminders and follow-ups for school work.

With the seemingly unending support of my parents, I built a studio and started producing music—without any tangible knowledge of how that is done. Fortunately, YouTube was my ally for the construction process, and my mother was my interior designer. I fantasized about what it would be to have a studio of my own, where I can get a team of people who are as passionate as me to make amazing music together. Slowly as the studio was being made, I found the right people to join the Compass Box Studio family. Through the work at the school, I knew how important it was for my mother to invest her time to create a team of people she can rely on to support the larger goal of education. I owe my team the same gratitude.

I can’t overstate the immense support I needed from my parents in order to see this through. I was very fortunate to have the safety net of my parents, to be able to explore such a drastic shift from teacher to music producer and studio owner.

In the last two years my studio has put out seven projects, of which some were in collaboration with NEXA Music, a platform for aspiring musicians, and composer Clinton Cerejo. Some of our work was featured on the best Indian EPs of 2019, some were nominated for awards at home and abroad. So, all in all, I’d say committing to my passion is less of a success, and more of a path under construction.

2020 has been a strange year for all of us. It’s an understatement to say that musicians aren’t coping well. For a profession that is not only sporadic in income, but tied to performances in venues with people, the pandemic has hit the industry hard.

At Compass Box Studio, we had started getting some sense of fame due to the live sessions—a series of one-take live recordings on YouTube of indie artists from all over India, recorded and produced at the studio, akin to Coke Studio. Since March, we have only recorded three live sessions, from six a month prior to this.

Music making requires a large number of people playing guitars, bass, drums, percussion, wind instruments. It needs engineers, mix and master engineers, singers, videographers, editors—the list is quite extensive. To downsize this and still have the same production quality is a challenge. With social distancing, we have to have as few people as possible when recording in a studio, while maintaining the integrity to the music we are making. We also had to re-evaluate who to call for the live sessions—because most of our artists come from outside Gujarat, and Ahmedabad, where we are based, doesn’t have too many musicians writing original music.

Passion becomes less of a driving force and more of a mediator in these times. It would’ve been easier to decide to stop the live sessions altogether and let the pandemic run its course, but we had to get work coming.

What allowed me to remain relatively unaffected for the most part was having a support system thanks to my parents, and work slowly resuming as people want more online content during this time.

In retrospect, there is a paradox in helping children find what they consider meaningful. You can either force them to do it with the hope that it’ll click, or leave them be, fully aware of the risk that it might take much longer and by that time it might be too late.

People say ‘passion’ fairly flippantly these days. They will say they are passionate about something without being diligent in seeing it through, because of all the fears of committing.

I have had the opportunity to see first-hand what passion can do to a person. It makes them obsessive like my father, and visionary like my mother. And I also realise that the core reason for doing more isn’t for fame, or success. It’s fundamentally joy. But that joy has to be taken in moderation, especially during a pandemic. Be easy on yourself in case you haven’t been able to pursue your passion because of Covid-19.

The definition of passion for me is having a father who’s obsession towards the sport drove him to be the best in the world, and a mother who won’t stop until she can give all children the world over a taste of what it’s like to say ‘I can’ (a movement created by her to provide the right tools and mentality for schools to believe in children and allow children to believe they can be agents of change). I was just lucky to see it first-hand.

“When you give space, you eliminate fear in a child's heart”: Kiran Bir Sethi

How to help your children find their voice, their path? Listen to Kiran’s ~4 minute audiogram, where she talks about how parents can give children the freedom and discretion to find their own voice and follow that with courage. “And that's when they find the hatt-ke (offbeat) career paths,” says.

Join Raag and Kiran on Saturday November 7, at 7.30 pm, for Season 2, Episode 5, of Talkin’ Bout My Generation.

If you haven’t registered to watch the show already, register here: https://bit.ly/FFTAMG